The Inheritance and Transformation of Modern Tea Culture

The Way of Tea, perfected by Sen no Rikyu during the Azuchi-Momoyama period, became established as a formal ritual within warrior society during the Edo period. After the Meiji Restoration, amidst major societal changes, it managed to survive and find new paths of development, centered around the iemoto (head of school) system.

A. The Edo Period: Diversification and Formalization

The Age of the Warrior: A New Style of Tea Ceremony

After the death of Sen no Rikyu, the spirit of his Way of Tea was inherited by daimyo (feudal lord) tea masters such as Furuta Oribe and Kobori Enshu. While basing their practice on Rikyu's wabi-cha, they each established their own unique tea styles, known as Daimyo-cha or Buke-sado (warrior tea ceremony), which reflected their personalities and the values of warrior society. For instance, Furuta Oribe pursued a bold and asymmetrical aesthetic known as "Oribe-gonomi" (Oribe's style), while Kobori Enshu created an elegant and balanced style celebrated as "kirei-sabi" (lit. "beautiful sabi"). The warrior tea ceremony also incorporated etiquette adapted for samurai, such as placing the fukusa (silk cloth) on the right side of the sash to accommodate their swords.

Meanwhile, Rikyu's grandson, Sen Sotan, revived the Sen family's Way of Tea, and his sons went on to found the three main Sen schools: Omotesenke, Urasenke, and Mushanokojisenke. This established the foundation of the iemoto (head of school) system, creating an organized structure for inheriting and teaching the Way of Tea.

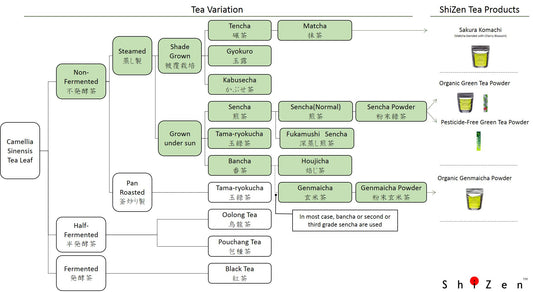

A Tale of Two Teas: The Rise of Sencha for the People

While Daimyo-cha and the warrior tea ceremony developed as a form of culture and ritual for the samurai class, a simpler tea culture spread among the townspeople. This was especially true after Nagatani Soen developed the "Aosei Sencha Method" in the 18th century, which led to the popularization of high-quality, beautifully green sencha. This formed another major stream of tea culture, distinct from the matcha-centric Way of Tea. Initially, commoners mostly drank coarse teas like bancha, but the spread of sencha made tea accessible to a much wider audience.

Oribe ware style pottery, characteristic of the warrior tea ceremony.

The development of Daimyo-cha in the Edo period can be seen as an attempt to inherit the spirit of Rikyu's wabi-cha while reconstructing it to fit the formalities and aesthetics of a peaceful warrior society. Oribe's dynamic beauty and Enshu's refined "kirei-sabi" showed the multifaceted potential of the Way of Tea, even as they moved in a different direction from Rikyu's introspective wabi. As the matcha-based tea ceremony became more advanced and specialized as a culture for the samurai and wealthy merchant classes, sencha became established as the daily beverage for the general public. This divergence in the cultural and social positioning of matcha and sencha continues to influence their respective images and consumption patterns today.

B. After the Meiji Restoration: Adaptation and Internationalization

Surviving the Restoration: The Tea Ceremony Finds New Purpose

The collapse of the feudal system during the Meiji Restoration brought great hardship to the world of tea, which had lost its daimyo patrons. However, the iemoto heads of schools overcame this crisis with clever strategies, adapting the Way of Tea to a new era. Initially, emerging financial conglomerates (zaibatsu) like Mitsui and Mitsubishi became the new patrons, and the tea ceremony survived as a hobby for the wealthy, with tea utensils being collected as art.

A more significant strategy was the introduction of the tea ceremony into women's education. It was incorporated as a regular or extracurricular subject in many girls' schools, and the certificates issued by the iemoto became valuable assets for women aiming to be "good wives and wise mothers." Through this, the tea ceremony, once a male-dominated culture, increasingly took on the aspect of being a form of cultivation and refinement for women.

During the Showa period, especially amid the rise of nationalism and militarism in the 1930s, the Way of Tea—and particularly Rikyu's spirit of wabi—was lauded as a symbol of Japan's unique spiritual culture and was used to promote national prestige.

Japanese women practicing the tea ceremony, Meiji period.

From an Emblem of Japan to a Global Ambassador

After World War II, the iemoto system faced another crisis but found a new path forward by positioning the tea ceremony as a means of international cultural exchange. It was promoted overseas as a symbol of a "cultural nation," Japan. Schools like Urasenke actively established overseas chapters and worked to introduce the Way of Tea to the world. The iemoto also began to diversify their operations into publishing, architecture, and even travel agencies.

Meanwhile, during the Meiji period, tea (especially green tea) became an important Japanese export. Production techniques and mechanization advanced, and quality improved, though there were times when domestic consumption was sidelined in favor of exports.

The evolution of the iemoto system is a prime example of how flexibly the Way of Tea has adapted to changes in social structures and values throughout history. Amidst the turmoil of the end of the samurai era, Westernization, nationalism, and postwar democratization and internationalization, the Way of Tea has maintained its core as a Japanese traditional culture while changing its meaning and target audience. The spread of tea ceremony among women, in particular, contributed greatly to maintaining and expanding the tea-practicing population, but it also placed the Way of Tea in a different social context than when it was centered around samurai and Zen monks. This gender shift continues to influence the image and practitioner base of the tea ceremony today.